A bit of history

Back in the 80s, 90s and the first years of 2000s, my primary computing environment was a 1980s-era IBM 8086 clone produced in the USSR. This machine was known as “ES-1841”. It had a whopping 640 Kb of memory, two 5 inch floppy drives and a small (can’t remember the size) HDD.

In the year 2002 I have finally switched to a Pentium III machine sporting Windows 2000. I was lucky that the new machine had compatible connectors for the 5 inch floppy drive. This allowed me to backup up most of the diskettes from my past. The result was a fat ZIP archive that I kept all these years.

Now, years later, nostalgia started to kick in and I was determined to restore my childhood environment using DOSBox (actually DOSBox-X since I needed more features that DOSBox could not handle.)

One of the sub-projects of this effort was the ability to open and view images we had created in the past using graphical editors. Unfortunately, I could not find any off-the-shelf product that can open some of the formats I was interested in, the most common being *.SCR.

So, I decided to create an application that will convert those files into *.BMP. What follows is the story of this effort.

Figuring out what they are

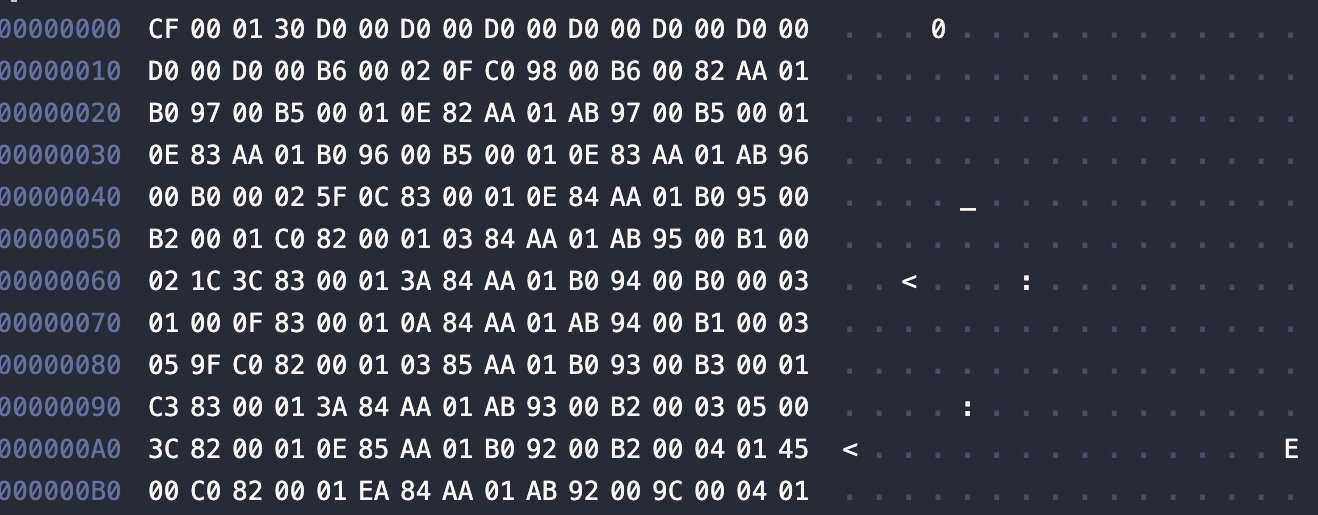

In order to begin decoding these files, first, I needed to understand what was their format. To be honest, in those days, formats were quite simple. Usually, image files only stored the binary dump of the video memory in a file. Some of formats might have had a header but that was rare. I opened one of the files in a Hex viewer and that was the output:

At a first glance it looks bare – no header. After opening a few other files it was noticed that all of them are a bit different, which confirmed my suspicion that they had no header.

Another clue was important - the file sizes were all different. This could only happen either due to different image sizes or due to contents being compressed somehow.

Lucky break

While looking through mounds of Pascal and x86 Assembly files written by me and my brother in the 1990s, I had a lucky find - a tool called CG0TOSCR. Cool! Apparently that’s something we had done. The CG0TOSCR.PAS apparently uses a unit (module) called PCISCR.PAS which calls some functions inside a PCISCR.ASM (x86 assembly) object file.

Opening PCISCR.ASM reveals a number of routines that are used for drawing on the screen and etc. Amongst those, there is a routine called GenerateScr:

GenerateScr proc far

push ds

push es

push si

push di

push cx

push bx

push ax

mov di,BuffOffs

mov ax,BuffSegm

mov es,ax

mov ax,0b800h

mov ds,ax

mov si,0 ;i:=0

mov bx,0 ;index:=0;

genscr_0: ;

cmp si,8000 ;

jge genscr_1 ;While i<8000 do

mov cx,0 ;count:=0;

push bx

mov bx,0

genscr_2:

mov ax,ds:[si+bx] ;while (mem[$b800:count+i]=mem[$b800:count+i+1])

cmp al,ah ;

jne genscr_3 ;

cmp bx,79 ;and (count<79)

jge genscr_3 ;

inc bx ;do inc(count);

jmp genscr_2

genscr_3:

mov cx,bx

pop bx

cmp cx,0 ;if count<>0 then

je genscr_4

mov al,byte ptr ds:[si] ;color:=mem[$b800:i];

inc cx ;count:=count+1;

add si,cx ;i:=count+i;

xor cx,80h

mov es:[di+bx],cl ;buff[index]:=count xor $80;

inc bx ;inc(index);

mov es:[di+bx],al ;buff[index]:=color;

inc bx ;inc(index);

jmp genscr_0 ;... goto while ...

genscr_4:

push bx

mov bx,0

genscr_5:

mov ax,ds:[si+bx] ;while (mem[$b800:count+i]<>mem[$b800:count+i+1])

cmp al,ah ;

je genscr_6 ;

cmp bx,80 ;and (count<80)

jge genscr_6 ;

inc bx ;do inc(count);

jmp genscr_5

genscr_6:

mov cx,bx

pop bx

mov es:[di+bx],cl ;buff[index]:=count;

inc bx ;inc(index);

genscr_7: ;for i:=i+1 to i+count do

mov al,ds:[si] ;

mov es:[di+bx],al ;buff[index]:=mem[$b800:i];

inc bx ;inc(index);

inc si

loop genscr_7

jmp genscr_0

genscr_1: ;end; While i<...

mov ax,ds

cmp ax,0b800h

jne genscr_8

mov ax,0ba00h

mov ds,ax

mov si,0

jmp genscr_0

genscr_8:

push es

pop ds

mov page0seg,bx

pop ax

pop bx

pop cx

pop di

pop si

pop es

pop ds

retf

GenerateScr endp

Look at that, it is even annotated with the Pascal code-like comments that was likely used to create it. OK, we’re onto something. So, what do we in this function? Well, it looks like it is taking the contents of the video memory at 0xb800:0000 and does some manipulation on it and places the result into BuffSegm:BuffOffs segment/offset pair.

The code listed below gives us a further clue:

genscr_2:

mov ax,ds:[si+bx] ;while (mem[$b800:count+i]=mem[$b800:count+i+1])

cmp al,ah ;

jne genscr_3 ;

cmp bx,79 ;and (count<79)

jge genscr_3 ;

inc bx ;do inc(count);

jmp genscr_2

This looks like a piece of an RLE encoder. But it looks a bit weird that it compares to 79 decimal and not 0x7F hex. Looking at the code further, confirms this is an RLE encoder, albeit a bit weird.

A refresher on RLE encoding

RLE encoding is a very simple way of compressing data which is likely to have long strings of identical bytes. This was very common in image files back in the days. For instance, if you had an image with a black horizontal like running from the start of the image to the end, then all the bytes would be 0x00. For a resolution of 320x200 with 2 bpp that would mean the line would be 80 bytes long. So instead of saving 80 zeros into the file it would make sense to compress them. RLE would see one store a control character followed by the number of repetitions and then by the byte that is repeated. For non-repeatable bytes, RLE would use another control character, followed by the number of non-repeating bytes and then the bytes themselves.

# For example, if we had 0x0000000000000000 value, we could encode it as follows:

0x01 0x08 0x00

^ ^ ^

| | +----- The repeated byte.

| +---------- The number of repetitions.

+--------------- The control character

# Or in case of non-repeating sequence of 0x0001020304050607:

0x00 0x08 0x010x020304050607

^ ^ ^

| | +---- The bytes as they are.

| +--------- The number of bytes.

+-------------- The control character.

Note that I chose 0x00 as control character for encoding repeating sequences and 0x01 for non-repeating.

We can actually optimize this further and save some bytes by combining the escape character and the number of (repeating) bytes into one single byte. We will designate 8th bit as escape bit and the remaining 7 bits as the count:

# For example, if we had 0x0000000000000000 value, we could encode it as follows:

0x88 0x00

^ ^

| +--------- The repeated byte.

+-------------- The control bit + number of repetitions.

# Or in case of non-repeating sequence of 0x0001020304050607:

0x08 0x020304050607

^ ^

| +--------- The bytes.

+-------------- The control bit + number of bytes.

Note that 0x88 is 10001000 in binary. If we clear the most significant bit we’re left with 0x08 which the count of bytes that need to be repeated.

This is the encoding used by the GenerateScr routine. It also means that we can at most encode 127 bytes per at a time.

A refresher into CGA

The “beloved” CGA was the one used in my old machine and it influenced a lot the format of the images themselves. The adapter used two pages of dedicated video memory. One was located at 0xb800:0000 and the other at 0xba00:0000. Both were 8000 bytes long.

There were two graphical modes we care about: 320x200 at 2 bpp (four colors), and 640x200 at 1 bpp (black and white). Both modes used exactly (320 * 200) / 4 = 16000 or 640 * 200 = 16000 bytes.

The primary complication came from the fact that CGA did row interlacing. What that meant in practice is that row 0 was located at 0xb800:0000 and row 1 was at 0xba00:0000 followed by row 2 at 0xb800:0050 and row 3 at 0xba00:0050, up to row 199. Each row was basically a horizontal line on the screen consisting of 80 bytes.

Looking at GenerateScr, it becomes clear that the RLE encoder goes through the first page at 0xb800:0000 and then starts encoding the second page at 0xba00:0000, though it seems to accidentally include more bytes at the end of each page for repeating sequences. Those bytes are just garbage and we will need to make sure we account for that in the decoder.

Another observation that needs pointing out is that we do not know what resolution and what color palette was used when saving those images into the files. That will need adjusting as we try to convert the images to Bitmap format. But more on that later…

Python time!

I have chosen Python for the decoder because it’s easy. It already has all the libraries I need and it’s akin to an “swiss army knife”. Also, I don’t need performance for this decoder.

The process itself can be structured into 4 steps:

- Load the file contents into a

bytearray, - Decode the RLE into two

bytearrays, one per page, - Render the bytes based on the CGA mode (

1bppvs2bpp), - Dump the contents into an output file.

Loading the file

The loading is quite straightforward:

def _get_bytes(in_file: str) -> bytes:

_logger.info(f"Opening file {in_file}...")

with open(file=in_file, mode="rb") as f:

res=f.read()

_logger.info(f"The original image is {len(res)} long.")

return res

Decoding the buffer:

Once we have the bytes loaded, we can now decode the input using the following function:

def _pad_buffer(b: bytearray, size: int):

rem=size-len(b)

if rem > 0:

b.extend([0]*rem)

def _expand_2p_rle(input: bytes) -> Tuple[bytearray, bytearray]:

i=0

pages=(bytearray(), bytearray())

page_size=8000

for page in pages:

while(i<len(input)):

if len(page) >= page_size:

break

cmd=input[i]

count=cmd & 0x7F

repeats=cmd & 0x80 == 0x80

i+=1

if count == 0:

_logger.warn(f"Encountered a zero count command {hex(cmd)} at {hex(i - 1)} (R={repeats}).")

page.append(0)

elif repeats:

if i == len(input):

_logger.warn(f"Encountered a repeat command for {count} at {hex(i - 1)} at EOF. Assuming 0x00.")

rep=0

else:

rep=input[i]

page.extend([rep]*count)

i+=1

else:

page.extend(input[i:i+count])

i+=count

_pad_buffer(pages[0], page_size)

_pad_buffer(pages[1], page_size)

return pages

You can see above, that:

- We start with the first

pagefrompagesand read the command byte. - Then we check if the most significant bit is

1. If that is true, then the next byte in theinputwill be repeatedcounttimes. Thecountis simply the last7bits of the command byte. - If the command byte’s most significant bit it

0then we need to readcountbytes from theinputas they are and copy them into thepage. - If the command byte is

0x00then we store it as it is into thepage. - This process is repeated until we reach

8000 bytes. Note that last command will encode some garbage leftover bytes from the0xb800segment which we need to discard. - After that we continue to the second page.

There are some issues in the original encoder so we sometimes need to pad the pages with 0x00 up to 8000 bytes.

The result of this decoding are two pages which need to be interleaved during rendering.

Resolution and palettes

Rendering is highly dependent on the chosen CGA mode. For 320x200 we will need to consider each byte consisting of 4 pixels. Each pixel is represented by 2 bits, amounting to 4 colors per pixel. CGA also has 6 palettes that can be chosen for this vide mode. Each palette attributes different colors values for the same bit combinations. For 640x200, though, each pixel takes 1 bit, which means that each byte will sport 8 pixels. That also means that there are only two colors per pixel - black and white.

To encode these choices, I have created a bunch of dicts:

CGA_black=[0x00, 0x00, 0x00]

CGA_dark_gray=[0x55, 0x55, 0x55]

CGA_blue=[0x00, 0x00, 0xAA]

CGA_light_blue=[0x55, 0x55, 0xFF]

CGA_green=[0x00, 0xAA, 0x00]

CGA_light_green=[0x55, 0xFF, 0x55]

CGA_cyan=[0x00, 0xAA, 0xAA]

CGA_light_cyan=[0x55, 0xFF, 0xFF]

CGA_red=[0xAA, 0x00, 0x00]

CGA_light_red=[0xFF, 0x55, 0x55]

CGA_magenta=[0xAA, 0x00, 0xAA]

CGA_light_magenta=[0xFF, 0x55, 0xFF]

CGA_brown=[0xAA, 0x55, 0x00]

CGA_yellow=[0xFF, 0xFF, 0x55]

CGA_light_gray=[0xAA, 0xAA, 0xAA]

CGA_white=[0xFF, 0xFF, 0xFF]

CGA_mode_4_palette_0_low={

0: CGA_black,

1: CGA_green,

2: CGA_red,

3: CGA_brown

}

CGA_mode_4_palette_0_high={

0: CGA_black,

1: CGA_light_green,

2: CGA_light_red,

3: CGA_yellow

}

CGA_mode_4_palette_1_low={

0: CGA_black,

1: CGA_cyan,

2: CGA_magenta,

3: CGA_light_gray

}

CGA_mode_4_palette_1_high={

0: CGA_black,

1: CGA_light_cyan,

2: CGA_light_magenta,

3: CGA_white

}

CGA_mode_5_palette_low={

0: CGA_black,

1: CGA_cyan,

2: CGA_red,

3: CGA_light_gray

}

CGA_mode_5_palette_high={

0: CGA_black,

1: CGA_light_cyan,

2: CGA_light_red,

3: CGA_white

}

CGA_mode_palette_6={

0: CGA_black,

1: CGA_white,

}

CGA_modes={

"CGA40L": {

"width": 320,

"height": 200,

"bpp": 2,

"palette": CGA_mode_4_palette_0_low

},

"CGA40H": {

"width": 320,

"height": 200,

"bpp": 2,

"palette": CGA_mode_4_palette_0_high

},

"CGA41L": {

"width": 320,

"height": 200,

"bpp": 2,

"palette": CGA_mode_4_palette_1_low

},

"CGA41H": {

"width": 320,

"height": 200,

"bpp": 2,

"palette": CGA_mode_4_palette_1_high

},

"CGA5L": {

"width": 320,

"height": 200,

"bpp": 2,

"palette": CGA_mode_5_palette_low

},

"CGA5H": {

"width": 320,

"height": 200,

"bpp": 2,

"palette": CGA_mode_5_palette_high

},

"CGA6": {

"width": 640,

"height": 200,

"bpp": 1,

"palette": CGA_mode_palette_6

},

}

This information is based on the Wikipedia article.

Rendering

Finally, rendering! Here we will take the two pages from the decoding step, and we will convert each byte into a set of pixels based on the resolution and bpp of the provided video mode:

def _render(pages: Tuple[bytes, bytes], width: int, height: int, bpp: int, color_map: Dict[int, list[int]]) -> "np.ndarray":

assert bpp in [1, 2, 4, 8]

bpb=8

ppb=bpb//bpp

output=np.ndarray(shape=(height, width, 3), dtype=np.uint8)

for h in range(0, height):

page=pages[h%2]

for w in range(0, width):

pi=(h // 2)*(width)+w

bi=pi//ppb

br=bpb-1-(pi%ppb)*bpp

ob=np.uint8(page[bi])

ob=np.left_shift(ob, np.uint8(bpb-1-br))

ob=np.right_shift(ob, np.uint8(bpb-bpp))

pix=color_map[ob]

output[h, w]=pix

return output

Woof! That’s a lot of bit manipulation going on here, but the short version is:

- Load each byte from each page,

- Divide the byte into pixels based on the

bpp, - Figure out the row and column for each pixel in the output,

- Apply the palette for each pixel based on the CGA mode,

- Store the color into the output 2D array.

This procedure works for any bpp which is less than or equal to 8 bits per pixel. Of course we only have much less bpps but why not do it right, eh?

All together

The final bit is to put all these things together:

# Load the file into memory

bts=_get_bytes(args.input)

# Select the CGA mode

mode=CGA_modes['CGA4LI']

# Expand the RLE

pages=_expand_2p_rle(raw)

# Render the image

img=_render(pages, mode["width"], mode["height"], mode["bpp"], mode["palette"])

# Save the image into the output file.

matplotlib.pyplot.imsave(args.output, img, format='bmp')

Africa unchained

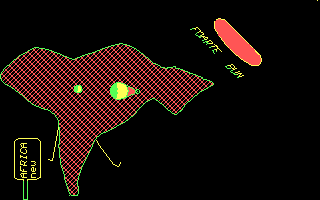

Finally we can show the image we were trying to decode:

Now that’s some art! Wouldn’t you agree? Totally worth the time.