And just when I thought I was done with converting old images into BMP format … another picture format attracted my curiosity.

For fun, read my previous post about decoding old-school SCR Images

Background

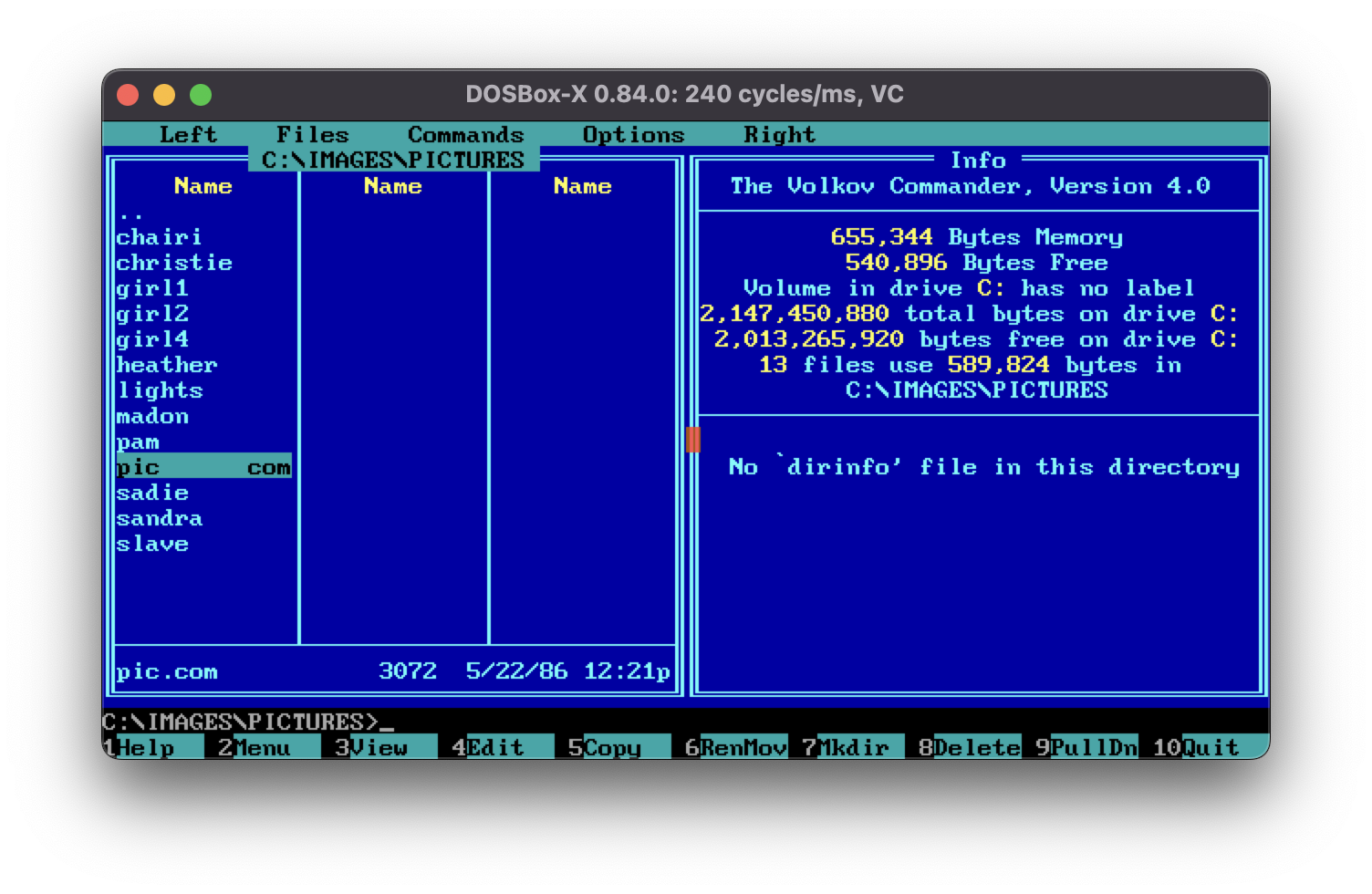

Looks like I have found a program that was used to print posters (maybe?). This program came with number of images in the package:

When ran,

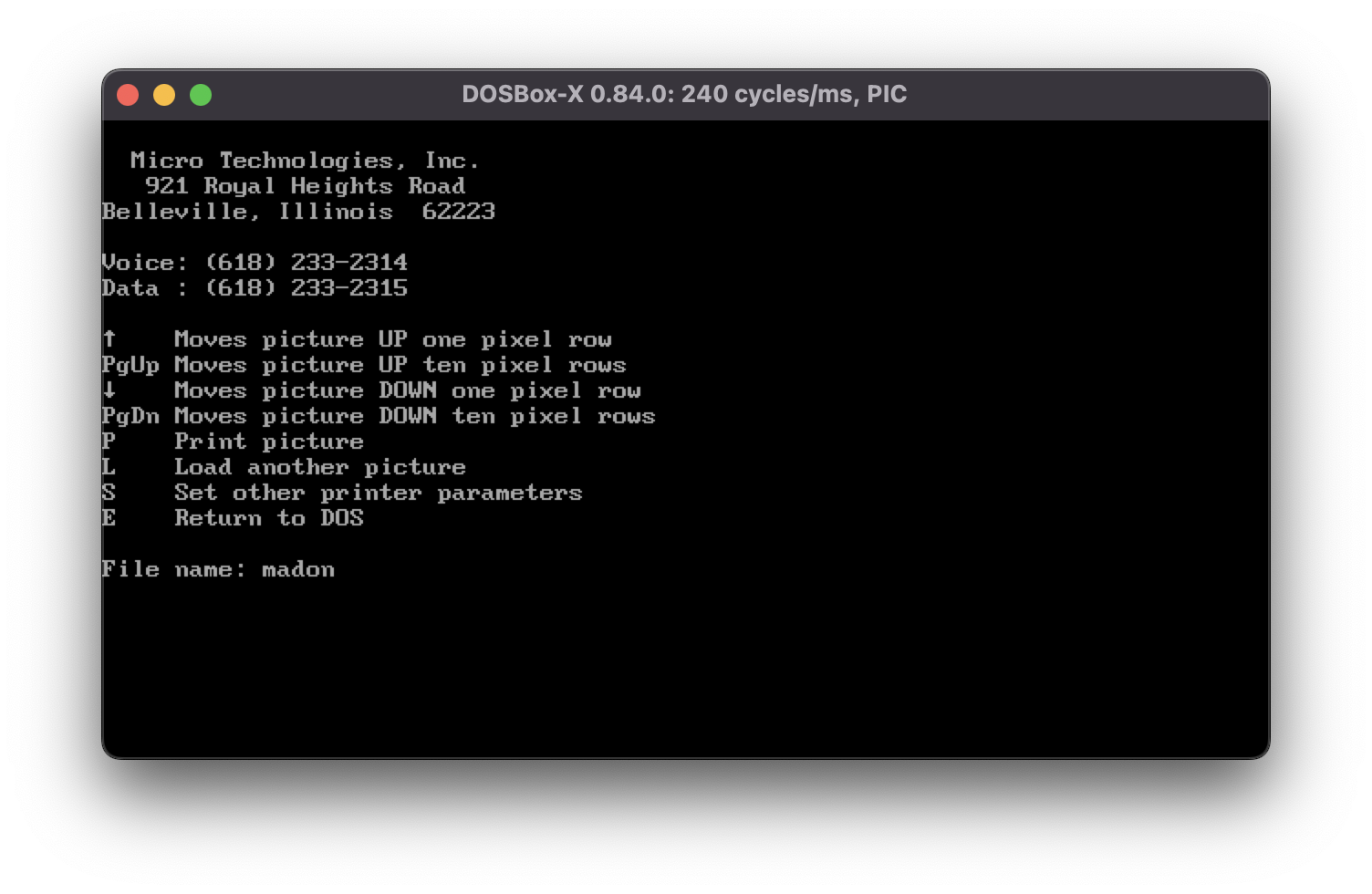

When ran, PIC.COM shows the following screen. We can type the file name we want to open:

And, when opening the

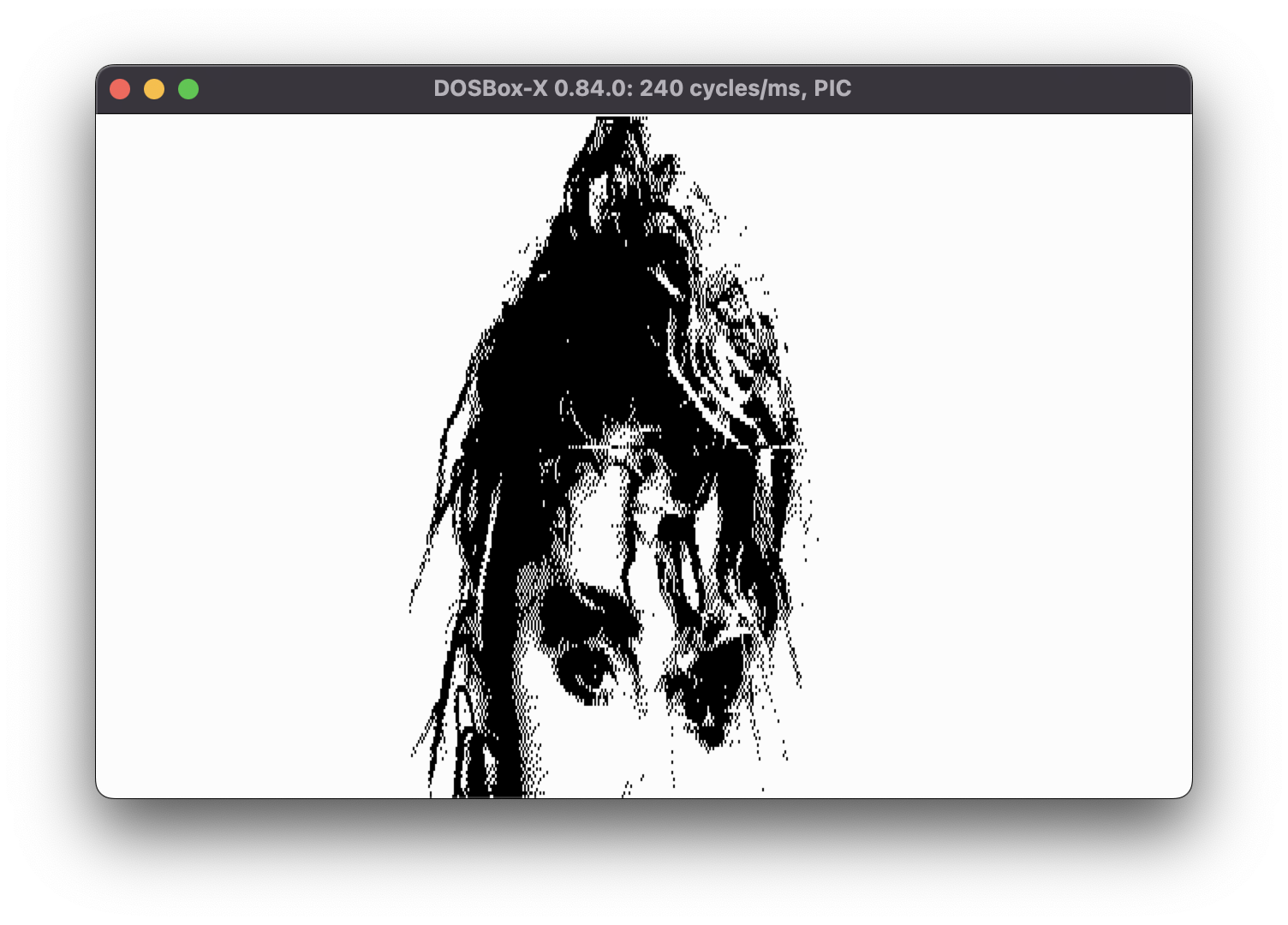

And, when opening the MADON file, we see a “Madonna” poster:

Using the arrow keys we can scroll the view up and get more details of the poster. Which means the image is larger than the actual view port.

Using the arrow keys we can scroll the view up and get more details of the poster. Which means the image is larger than the actual view port.

The program also seems to use 640x200 resolution. As a reminder, this resolution sports a whopping 1 bpp with only black and white colors.

The file structure

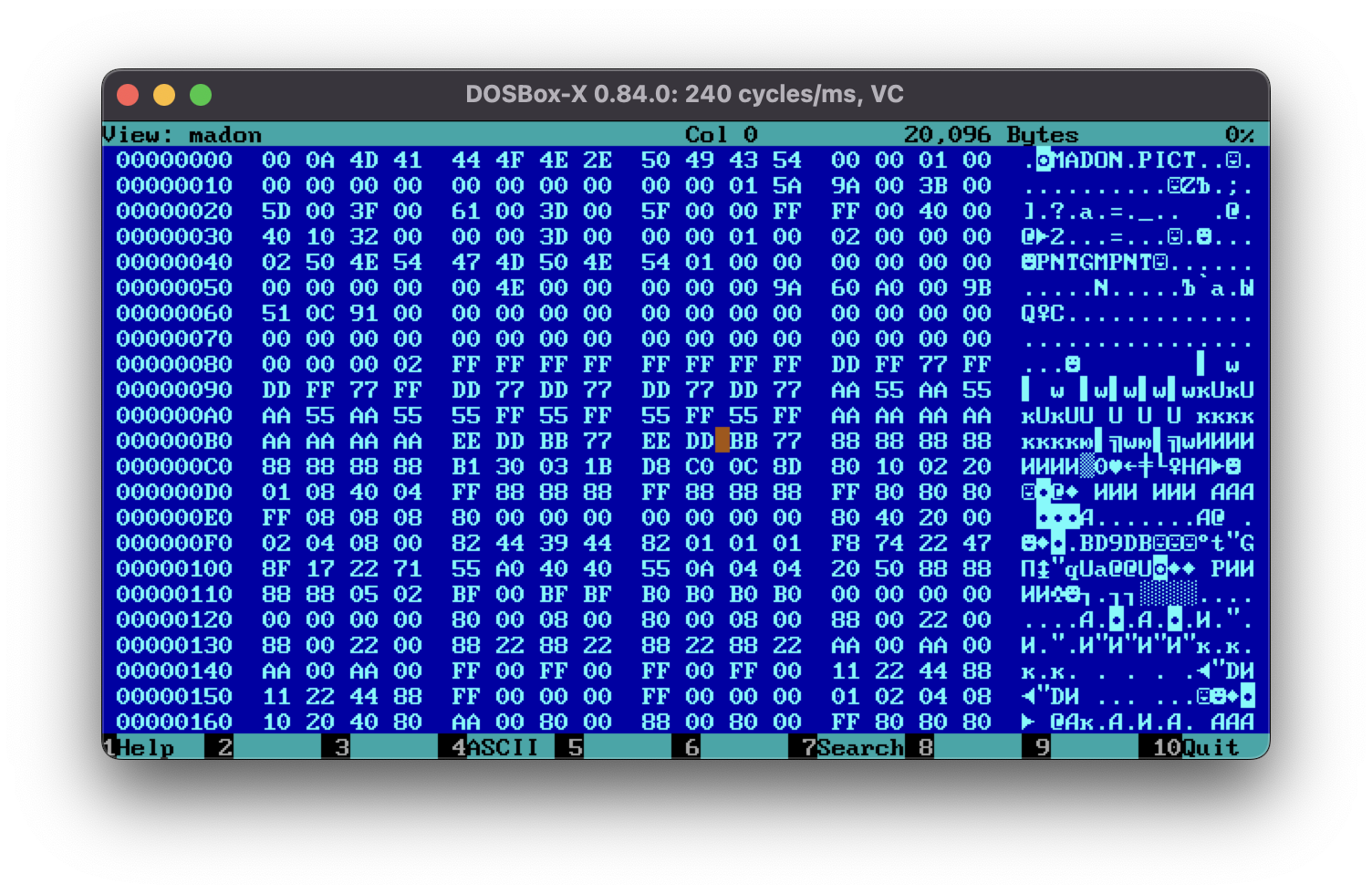

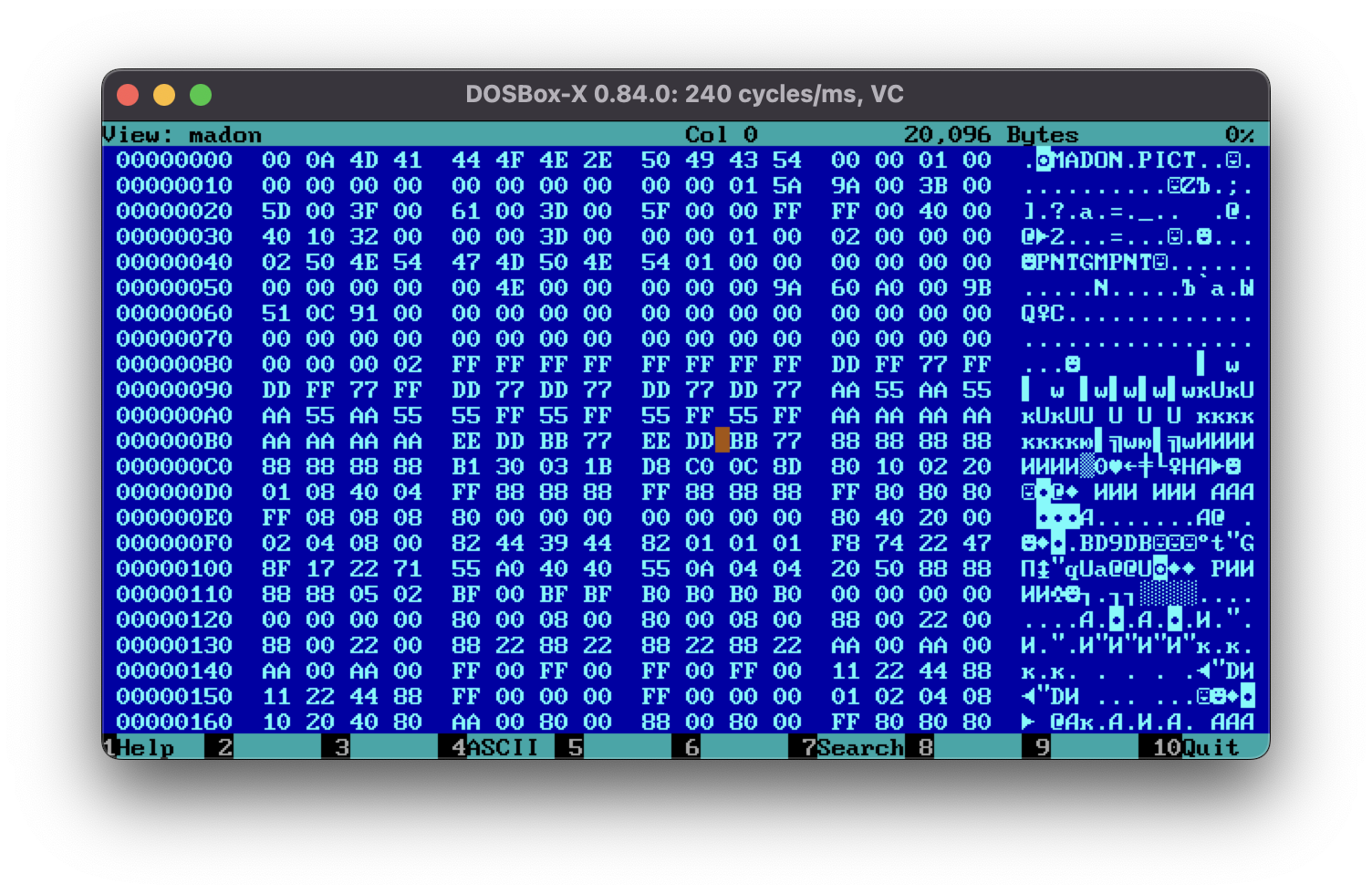

Following the existing procedure, let’s see what the file format is. To achieve that we need to see its hex view:

Hm, interesting. This file seems to actually have a header. That might make the decoding a bit more complicated as this means that the header might contain image data size or any other meta information required to decode it. Also the file sizes are all different which, can point to a compression format.

Hm, interesting. This file seems to actually have a header. That might make the decoding a bit more complicated as this means that the header might contain image data size or any other meta information required to decode it. Also the file sizes are all different which, can point to a compression format.

Reversing the executable

To be honest I have no idea how to approach this format and I the most reasonable way of proceeding would be to study the source code of the PIC.COM utility.

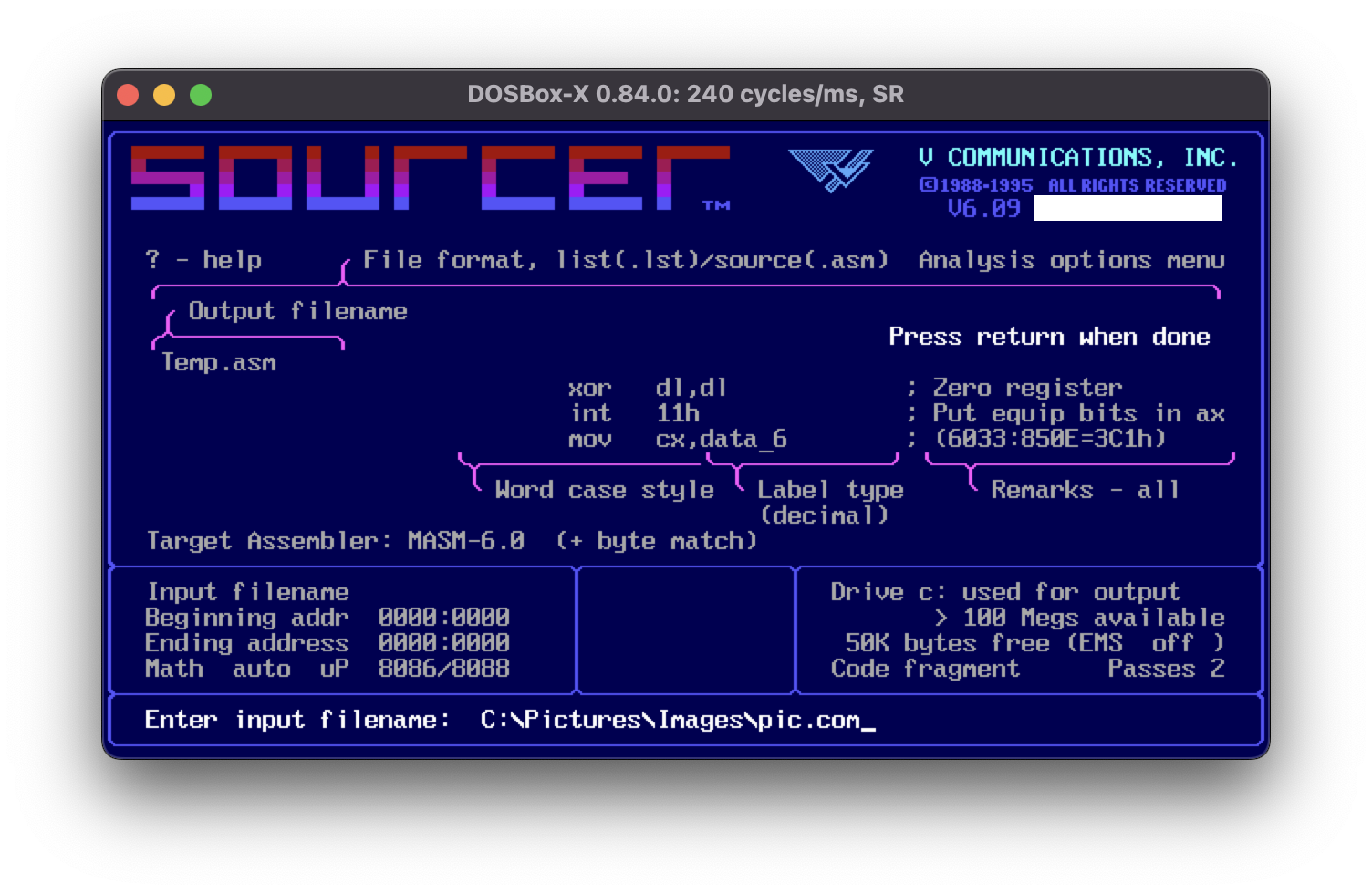

To achieve that, I have the amazing DOS program called Sourcer which I found lying around my DOS-era archives:

In the above screenshot, we select the output format of the dec-compiled source as MASM-compatible assembly language and select the input file.

As side note, check out the cool UX that this program sports. I just love it!

The output of running Sourcer is a nice PIC.ASM file that has been annotated and ready to be looked at. Here is a small snippet:

;��������������������������������������������������������������������������

;

; External Entry Point

;

;��������������������������������������������������������������������������

real_start:

push ax

push bx

push cx

push dx

push si

push di

push ds

push es

push cs

pop ds

call sub_11

lea bx,cs:[0BE3h] ; Load effective addr

mov cs:image_buffer_ptr,bx

loc_1:

mov ax,3

int 10h ; Video display ah=functn 00h

; set display mode in al

mov ax,600h

mov bh,7

mov cx,0

mov dx,184Fh

int 10h ; Video display ah=functn 06h

; scroll up, al=lines

; bh=attrib, cx+dx=window size

lea dx,data_8 ; ('') Load effective addr

mov ah,9

int 21h ; DOS Services ah=function 09h

; display char string at ds:dx

lea dx,data_15 ; Load effective addr

mov ah,0Ah

int 21h ; DOS Services ah=function 0Ah

; get keybd line, put at ds:dx

mov al,cs:data_16

mov ah,0

mov si,ax

mov cs:data_17[si],0

mov byte ptr cs:data_14[si],24h ; '$'

mov cx,si

mov si,zero

The rendering process

Note how Sourcer has named the memory locations using data_xx names. That’s to be expected since we do not have debug symbols and the de-compiler simply attributed random names to each memory location and sub-routine.

This means that the only way to understand the actual code is to look at it, and replace these auto-generated names with the actual names as we go along.

My process is simple. when I understand the purpose of a memory location/variable/sub-routine, I simply replace that name with something more readable based on its purpose.

But, first things first, where is the sub-routine that draws on the screen? The way to approach that is to find the code that references the CGA video memory segment 0xb800. Searching the file we immediately find the following sub-routine:

sub_7 proc near

push ax

push bx

push cx

push dx

push si

push di

push bp

push es

mov ax,0B800h ; <------ CGA VIDEO MEMORY REFERENCE

mov es,ax

mov bp,data_51e

mov ax,cs:data_38

mov si,48h

mul si ; dx:ax = reg * ax

add ax,cs:data_37

mov bx,ax

mov cx,64h

locloop_57:

push cx

mov si,data_1e

mov di,data_51e

mov cx,48h

locloop_58:

mov al,[bx+si]

xor al,0FFh

mov es:[bp+di],al

inc si

inc di

loop locloop_58 ; Loop if cx > 0

add bx,data_7e

add bp,50h

pop cx

loop locloop_57 ; Loop if cx > 0

mov bp,data_52e

mov ax,cs:data_38

mov si,48h

mul si ; dx:ax = reg * ax

add ax,cs:data_37

mov bx,ax

add bx,48h

mov cx,64h

locloop_59:

push cx

mov si,data_1e

mov di,data_51e

mov cx,48h

locloop_60:

mov al,[bx+si]

xor al,0FFh

mov es:[bp+di],al

inc si

inc di

loop locloop_60 ; Loop if cx > 0

add bx,90h

add bp,50h

pop cx

loop locloop_59 ; Loop if cx > 0

pop es

pop bp

pop di

pop si

pop dx

pop cx

pop bx

pop ax

retn

sub_7 endp

We can separate this sub-routine into two parts:

- From the

mov ax,0B800htoloop locloop_57, the code draws the picture into the first page of the CGA video memory, - And from

mov bp,data_52etoloop locloop_59, the second page. The value ofdata_52eis0x2000.

For each page it looks as there are two loops. I won’t try to go through each line of the assembly, though as there’s too much to follow. Instead, here’s the pseudo-C code of this function:

int video_memory = 0xb800 // first memory page at 0xb800

for (row = 0; row < 200; row += 2) {

for (col = 0; col < 72; col++) {

int pix8 = image_bytes[scroll_index + (row * 80) + col] ^ 0xff

video_memory[row * 80 + col] = pix8

}

}

video_memory = video_memory + 0x2000 // next memory page

for (row = 1; row < 200; row += 2) {

for (col = 0; col < 72; col++) {

int pix8 = image_bytes[scroll_index + (row * 80) + col] ^ 0xff

video_memory[row * 80 + col] = pix8

}

}

Right, so what’s with all these magic numbers: 72 (0x48), 200 (0x64 * 2), 80 (0x50) and why are we XOR-ing with 0xff? Remember that each row is 640 pixels? That translates to 640 pixels / 8 ppb = 80 bytes. But why are we only copying 72 bytes into the video memory? Well that’s up to the original developer; apparently the width of these images is 72 bytes * 8 bpp = 576 pixels. The height of the same video mode is 200 pixels which explains the loops.

The file format

Since we have identified the rendering function, now we need to figure out what is the actual file format. In the previous section, the memory at data_37 is the actual raw image bytes which are being copied into the video memory. The data_38 is the vertical offset in the image to copy into the video memory (remember, one can scroll up and down using arrow keys).

Looking further into the source code there’s a few sub-routines that stand out:

sub_9 proc near

push dx

lea dx,data_17 ; Load effective addr

mov ax,3D00h

int 21h ; DOS Services ah=function 3Dh

; open file, al=mode,name@ds:dx

mov cs:data_18,ax

pop dx

retn

sub_9 endp

This one seems to open the input file and store the handle into data_18 memory location. Following that variable we find:

sub_10 proc near

push bx

push cx

push dx

mov ah,3Fh ; '?'

lea dx,data_19 ; Load effective addr

mov cx,80h

mov bx,cs:data_18

int 21h ; DOS Services ah=function 3Fh

; read file, bx=file handle

; cx=bytes to ds:dx buffer

mov cs:data_35,0

pop dx

pop cx

pop bx

retn

sub_10 endp

This one seems to read 128 (0x80) bytes from the input file into data_19 memory location; and resets another memory location at data_35 to 0. Let’s follow the thread further:

sub_8 proc near

push si

mov si,cs:data_35

cmp si,80h

jl loc_61 ; Jump if <

call sub_10

mov si,data_1e

loc_61:

mov al,cs:data_19[si]

inc cs:data_35

pop si

retn

sub_8 endp

Alright, here they seem to be returning a byte from the buffer filled in by sub_10. If the read byte exceeds 128 (0x80), this sub-routine calls the aforementioned sub_10 to load more bytes. This explains why data_35 is set to zero in sub_10. It’s basically an index into the buffer which needs to be refilled at each 128 bytes.

It makes sense to find the uses of sub_8 and sub_10. The following code is found at some point when the name of the file is entered by the user:

lea dx,data_12 ; ('') Load effective addr

mov ah,9

int 21h ; DOS Services ah=function 09h

; display char string at ds:dx

call sub_9

jnc loc_3 ; Jump if carry=0

lea dx,data_13 ; ('') Load effective addr

mov ah,9

int 21h ; DOS Services ah=function 09h

; display char string at ds:dx

jmp loc_25

loc_3:

call sub_2

mov cx,5

locloop_4:

call sub_10

loop locloop_4 ; Loop if cx > 0

This code calls sub_9 which opens the file and stores the handle, then, it calls sub_2 and then, calls sub_10 5 times in a loop. sub_2 seems to simply clean up the memory location where the image contents will be loaded and sub_10 called 5 time will basically skip the first 4 * 128 = 512 bytes. Looking at the hex view again, it seems that it might correspond to the header part of the file:

This seems to indicate that

This seems to indicate that PIC.COM simply ignores the header!

The following piece of code finally reveals the last piece of the puzzle (cleaned for clarity):

mov cs:data_35,80h

mov cx,2D0h

mov bx,cs:data_37

locloop_5:

mov si,0

mov cs:data_34,0

push cx

loc_6:

call sub_8

cmp al,0

jl loc_8 ; Jump if <

mov ah,0

mov cx,ax

inc cx

locloop_7:

inc cs:data_34

call sub_8

mov [bx+si],al

inc si

loop locloop_7 ; Loop if cx > 0

jmp short loc_10

db 90h

loc_8:

mov cl,al

mov ch,0

mov ax,100h

sub ax,cx

mov cx,ax

inc cx

call sub_8

locloop_9:

inc cs:data_34

mov [bx+si],al

inc si

loop locloop_9 ; Loop if cx > 0

loc_10:

mov ax,cs:data_34

cmp ax,48h

jl loc_6 ; Jump if <

pop cx

add bx,48h

loop locloop_5 ; Loop if cx > 0

The pseudo-C version of this code is:

for (int row = 0; row < 720; row++) {

int col = 0;

while (col < 72) {

int count = read_next_image_byte()

if (count < 0) {

// if count is negative, transform to positive and assume the next

// byte repeats these many time plus one.

count = -count

int value = read_next_image_byte()

while (count >= 0) {

image_bytes[row * 72 + col] = value

col++

}

} else {

// if the count is positive, read said amount of following bytes plus one from the file.

while (count >= 0) {

image_bytes[row * 72 + col] = read_next_image_byte()

col++

}

}

}

}

Oh well, look at that. Another RLE decoder. Seems to decode each row of 72 bytes individually and assumes that there are always 720 rows.

Show me the code!

Alright, enough research, let’s write that python code again. I have actually reused much of the existing code used in the previous decoding attempt so this one will be easier to carry out.

First, the *RLE decoder:

def _expand_comp_rle(input: bytes, start: int, row_len: int) -> bytearray:

i=start

output=bytearray()

row=bytearray()

while i <len(input):

if len(row) >= row_len:

output.extend(row)

row.clear()

cmd=input[i]

repeats=(cmd & 0x80) == 0x80

if repeats:

count=0x100-cmd

else:

count=cmd

count +=1

i+=1

if repeats:

if i == len(input):

_logger.warning(f"Encountered a repeat command for {count} at {hex(i - 1)} at EOF. Assuming 0x00.")

rep=0

else:

rep=input[i]

row.extend([rep]*count)

i+=1

else:

row.extend(input[i:i+count])

i+=count

if len(row):

output.extend(row)

return output

This is the same code as the pseudo-C above. The start and row_len are used to control the decoding part (maybe will use in the future). The count=0x100-cmd line is equivalent to count=-count.

Now, the code that actually pulls things together follows as:

def _process_pic(raw: bytes, width: int, height: int, bpp: int, palette: dict[int, int]) -> np.ndarray:

pages=(bytearray(), bytearray())

HEADER=0x80*5

ROWS=720

COLS=72

raw=_expand_comp_rle(raw, HEADER, COLS)

for row in range(ROWS):

page=pages[row%2]

for col in range(COLS):

byte_index=row*COLS+col

if byte_index >= len(raw):

break

col_byte=raw[byte_index]^0xff

page.append(col_byte)

_pad_buffer(pages[0], 0x2000)

_pad_buffer(pages[1], 0x2000)

mode=CGA_modes['CGA6']

return _render(pages, COLS * 8, ROWS, mode['bpp'], mode['palette'])

And, finally, just in the previous blog post, we can simply export the 2D ndarray to a bitmap:

Disclaimer

It actually took me a good few hours while on a long cross-Atlantic flight to figure out the

PIC.COMcode and reinterpret it as python code.

Hope you enjoyed the post, Cheerios!